The Noller Lab

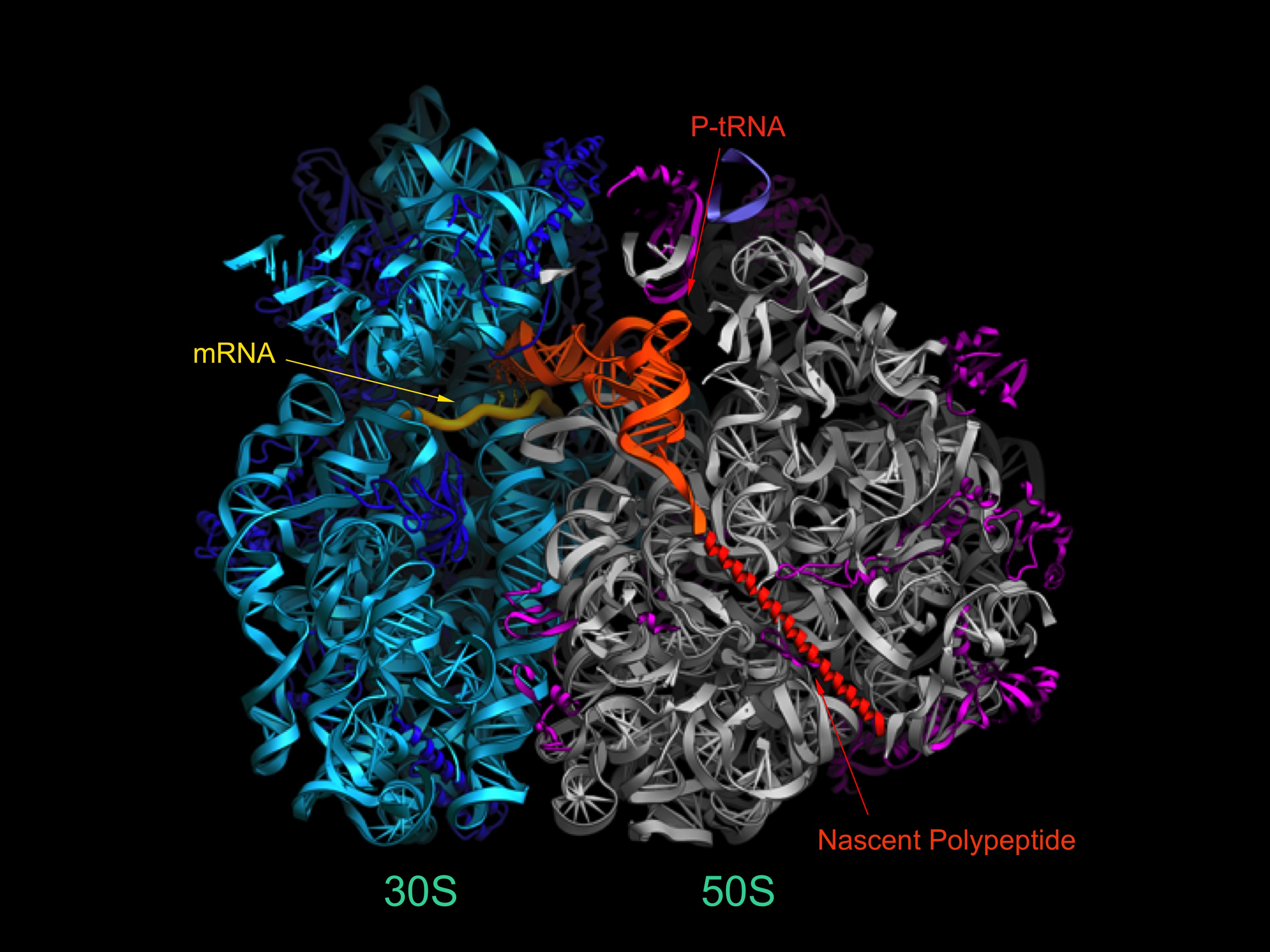

The ribosome is a very large (~2.5 MDa) cellular ribonucleoprotein complex responsible for translation of the genetic code, and synthesis of proteins in all organisms. The Noller lab uses a wide range of experimental and computational approaches, including x-ray crystallography, single-molecule FRET, genetics and biochemistry to study the structure and mechanisms of action of this ancient macromolecular machine. Most intriguing is the overwhelming evidence that the core biological functions of the ribosome, including aminoacyl-tRNA selection, peptide bond formation and translocation, are based on its ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

An example of a current area of investigation is to understand the mechanism of translocation - the coupled movement of mRNA and tRNA through the ribosome during the elongation phase of protein synthesis. How are the tRNAs, with molecular weights of ~25 kDa, transported precisely through the ribosome at rates of ~20 sec-1 over distances of 20-70 Å ? And how is this accomplished while rigorously maintaining the translational reading frame? The first indications are that translocation is driven by movement of structural elements of the ribosome itself. This view raises further questions: what are the ribosome’s moving parts, how do they move, how are these movements coordinated and how do they enable the mechanisms of translocation? One approach to understanding the structural dynamics of the ribosome is to determine crystal structures of the ribosome trapped in intermediate states of translocation. Another approach is the use of Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) - to watch the movements of fluorescent labels attached to specific positions of the ribosome structure during translocation in real time. We are also using computationally-based comparative structural analysis to understand the stereochemical basis of ribosome structural dynamics. Mechanistic models are then tested by directed mutagenesis of key structural elements. The emerging view is that the unique dynamic properties of RNA may account for its participation in the core functions of the ribosome.

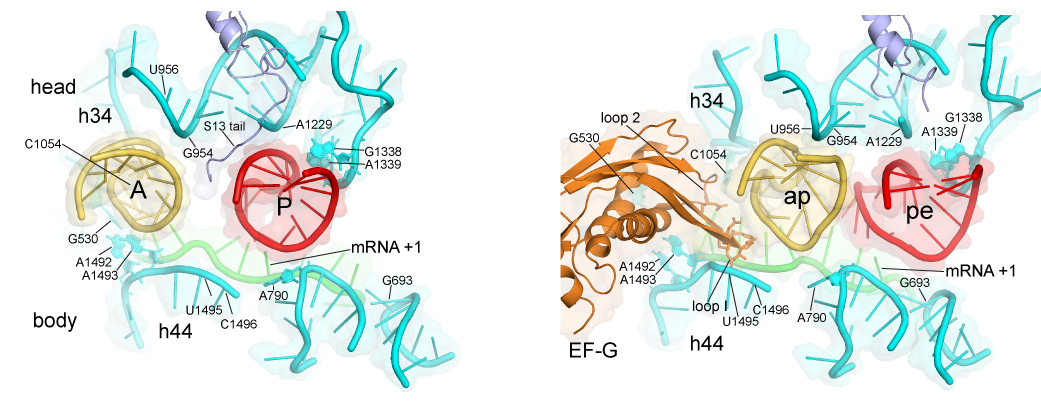

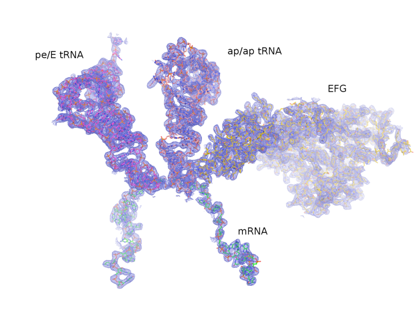

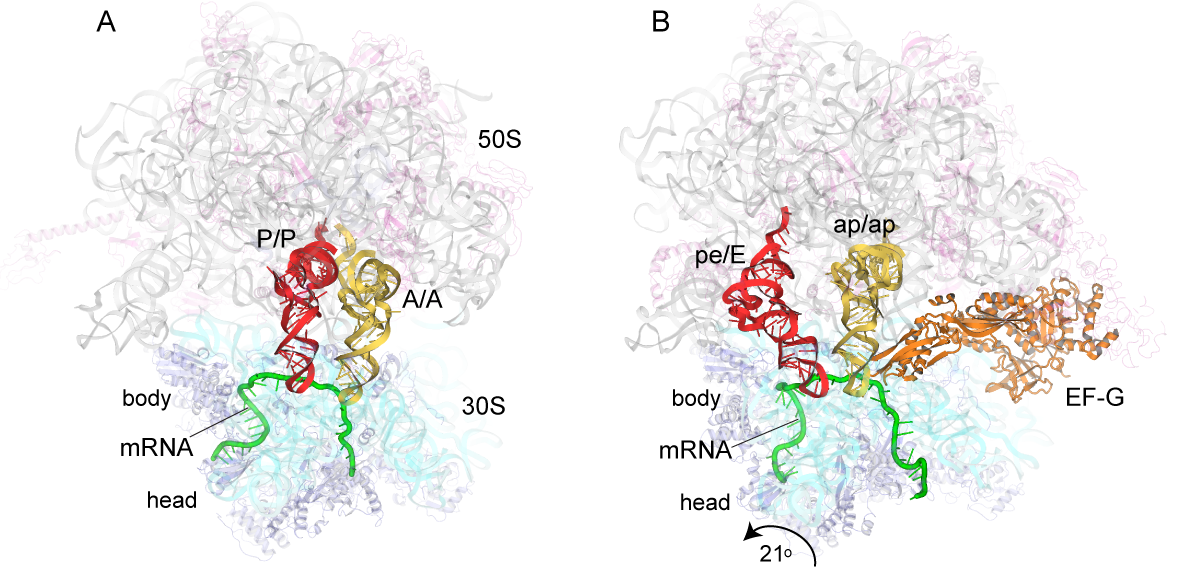

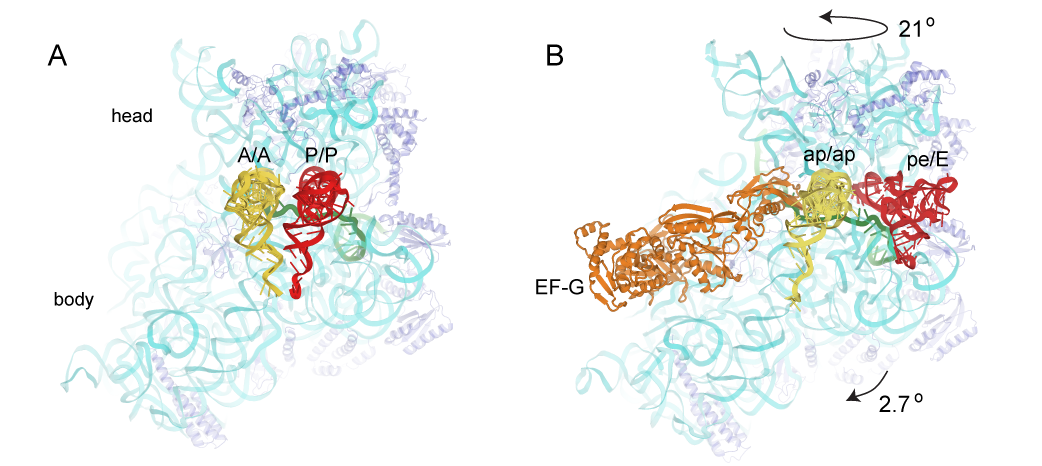

A working model is that in the first step of translocation, the tRNAs move relative to the large ribosomal subunit. In this step, the acceptor end of the A-site and P-site tRNAs move into the P and E sites, respectively, of the large subunit, creating the A/P and P/E hybrid states. This step can proceed spontaneously, driven purely by thermal energy, and is reversible. In the second step, the mRNA and the anticodon ends of the tRNAs move relative to the small ribosomal subunit, creating the classical P/P and E/E states, completing translocation. Head Rotation Positions of tRNAs in (A) the classical-state ribosome (Jenner et al., 2010) and (B) a trapped chimeric hybrid-state translocation intermediate, showing contact between domain IV of EF-G and the mRNA and ap/ap chimeric hybrid-state tRNA (Zhou et al., 2014). This step is the main kinetic and thermodynamic barrier to translocation, and is overcome by elongation factor EF-G, a GTPase. The first step is accompanied by rotation of the small subunit relative to the large subunit, and the second step by rotation of the head domain of the small subunit. However, in spite of considerable progress on this problem, many fundamental questions remain unanswered, including: What is responsible for the energy barrier to the second step of translocation that is overcome by EF-G and GTP? How does EF-G overcome this barrier? How do the 30S subunit head and body reverse without reversing tRNA movement? What is “the ratchet”? What is the pawl of the ratchet? Does EF-G bind to the classical or hybrid state? What does GTP hydrolysis accomplish? How does EF-G promote intersubunit and head rotation? What prevents shifting of the translational reading frame during translocation? Is mRNA actively translocated, or is it moved by its association with tRNA? And, how is movement of all of the various structural elements coordinated?